Hurley Wilvert was a mechanic and amateur racer who earned his shot at the big time in the early 1970s. By 1974, he was on the podium of the Daytona 200 with Giacomo Agostini and Kenny Roberts. Norm DeWitt tells his fascinating story.

Words: Norm DeWitt Photographs: Norm DeWitt and Jan Burgers

Hurley Wilvert was born in Pennsylvania, one of many in the immediate post Second World War generation who was constantly being relocated, his father being in the Army.

Hurley takes up the story, “I was born in Sunbury, but didn’t live there long, maybe until I was five; my Dad was gone most of the time. After the war he was an officer in the Army Corps of Engineers.

“One of his tours was in Orleans, France in the mid-50s, so the whole family moved there. Everyone rode mopeds. He bought me one for Christmas 1957, a brand new Solex moped with the motor over the front wheel. I probably put 10,000 miles on that bugger.”

Hurley left for College in 1962, and marriage/family soon followed. “I got a job in Louisville, Kentucky in 1964 and wanted a motorcycle. I bought an S65 Honda and I rode it to work.

“I moved to Cincinnati because I wanted to finish my degree in mechanical engineering. There I got the bug for a bigger bike and I finally decided on the Suzuki X6… a 250 twin two-stroke. The horn wasn’t very loud so I went to the dealership; Suzuki of Cincinnati was a real dive.

“I told the owner that I wanted a horn replaced, so he digs around in the box and says… ‘nah, I don’t have a horn, I’ll have to order one for you.” Hurley borrowed some tools and after turning the screw the horn got sufficiently loud, the dealer said… ‘How did you know how to do that? Do you want a job?’ So he hired Hurley as his night-time service writer.

“That year Walt Fulton won the Daytona Novice race on a Suzuki X6, and of course we heard all about it. I thought it would be so cool to be able to race like that. But I didn’t do anything about it, didn’t know anybody involved with racing. It was on the back burner until I moved to California in 1965, trying to find a job in the motorcycle industry.

“I went to Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki, and Honda; they all said I didn’t have enough experience. I ended up buying a 350 Bridgestone in Long Beach and decided I was going to race. The dealership was sponsoring Jerry Green in the AFM 350 production class, so I went to the races and got to be friends with him.

“I figured if he could do that, I could too. So, I screwed my bike down for racing and found out that I was competitive right away. I didn’t really know what I was doing but I could go fast. In the AFM there was Steve McLaughlin, Ron Grant, Art Baumann, and Ralph White.

BIG BREAKS

Within a couple of years the breaks started to happen. “I was the service manager for Pacific Coast Honda in Lomita. When the Honda 750 first came out, my dealer decided they wanted me to race it, as I’d done well with the 350 Bridgestone, an A1R Kawasaki for 250GP, and a Honda CR93 in 125GP.

“The 750 was definitely a jump up and there was an AFM Ultra-Production class for big bikes in 1969-70. Bill Manley and Jack Simmons were big flat track racers from Ascot and the AMA, and they road-raced the Norton Commando when it first came out.

They would come around corners with the back end pitched out, and I thought “what?” So I tried doing that with the Honda, and ended up beating them at Carlsbad.”

Hurley’s big break came later that year, from Norm Reeves Honda-Kawasaki in Bellflower. “That’s when the Kawasaki H1Rs came out. One of my neighbours worked for Norm Reeves and he convinced Norm that he should buy an H1R and let me ride it.

“I think I crashed it the first time I rode it, but ended up doing pretty well on it.” The breakthrough on the H1R came at Orange County International Raceway. A big FIM race was there in 1970. Don Emde, Ralph White, Jody Nicholas were there and I ended up winning.”

Don Emde remembers, “Jody (Nicholas) and I had an epic battle for the lead and I over revved my 350 a bit to stay with his 500 Suzuki. Then late in the race Jody crashed and I had it won, but about a lap or so to go my motor gave up the ghost with the lower connecting rod bearing burned out. So Jody and I were out and Hurley cruised to victory. I remember Cycle News or Motorcycle Weekly ran a headline of the race: ‘Hurley Who?’ I’d say that win kind of put him on the map.”

Hurley again: “After that I decided to start racing AMA, and had a mechanic, Steve Whitlock. The first race was at Loudon and I think I finished 14th; the next race was Talladega. I had not seen any of those Super Speedways before and it was just mammoth.

“Even Riverside looked small in comparison. Unfortunately I ended up crashing there. I learned about gas stops and how the suspension goes down further. I didn’t compensate, dragged a pipe and crashed. It was a pretty reliable bike, it wasn’t picky about which cylinder; it would seize on any of them.”

The Norm Reeves ride began to go away, with no further AMA Nationals in 1970, ending with the Daytona 200 in 1971. “I rode an H1R, the chain broke. Phil Read was there with the John Player Norton. I was the length of the back straight behind Read when the chain broke and Read ended up finishing fifth so I would have been in the top 10.

“Next I bought a 350 Yamaha TR-2. I raced in the AMA at Seattle and Ontario. I got an H1R for Daytona from Wes Cooley Senior, but it seized. We didn’t have any fuel filters on it and a blade of grass got into the carburetor and blocked the main jet.

“It was very depressing as I was out of money. I came back home and was ready to quit when Steve Whitlock called. Steve had gone to work for Bob Hansen for 1972, and he said ‘I don’t know if you are interested but Bob is looking for a mechanic for this English guy, Paul Smart. Would you be interested in doing it, I know you are hard up for money.’ I went right over there and started working on Paul Smart’s H2R.”

TEAM HANSEN

“Paul and I had a pretty good working relationship. The bike consistently finished, usually in the five. We kept trying to improve the bike and by the time we got to Ontario I’d worked my ass off. We’d gotten a Seeley frame and Paul ended up winning. It was the biggest paying motorcycle road race ever held up to that time.

“Paul used to tell people that I was the guy that made him rich; he did most of it, but we made out good in that race. But Paul didn’t get along that well with Bob Hansen, so he decided to get a deal at Suzuki for 1973. I was expecting to go with Paul to Suzuki as his mechanic but it didn’t work out.

“Bob Hansen wanted me to be Yvon Duhamel’s mechanic the next year but I saw Paul Smart’s old bike and I thought I could ride that. It was kind of a dirty trick on Bob, who was one of the best bosses I ever worked for, but Bob went out of town so that week I made a resume and photos with a presentation to Sid Saito, who was in charge of Kawasaki R&D to let me run Paul’s old bike. Sid let me do it.”

Needless to say that move went over like a sack of bricks on Hansen’s return. “He was definitely not pleased and didn’t talk to me for about two months. My deal with Sid was that he would provide me with parts and Bob made sure that only stock bike parts were available. I ended up getting used parts from the other guys.

“My contract said they had to supply me with tyres and Goodyear had this weird slick that didn’t have much grip. It made the bike handle even worse. The other Kawasakis were on Dunlop but Bob made me use the Goodyear because he got them for free. I had spoked not mag wheels, so they had to put a tube in it. Racing at Daytona in 1973, I was running well when I got a flat tyre from a pinched tube.”

The next race was in Texas, where Hurley finished seventh behind Don Castro, Gary Fisher, Geoff Perry, Kenny Roberts, Gary Nixon (the first Kawasaki), and Paul Smart won on the Suzuki. “After that, Bob Hansen became more friendly and started talking to me. Over the rest of the year, he definitely loosened up. Eventually I ended up with Dunlop tyres and mag wheels.”

Eighth at Road Atlanta and sixth at Loudon followed. “At Pocono I was running second behind Gary Nixon near the end of the race and ahead of Kenny Roberts, when the rod bearing on the used crankshaft went. Then at Charlotte, near the end of the year, I got third behind Duhamel and Roberts.”

As with the soft-spoken Pat Hennen who was just coming onto the scene, Wilvert let his results speak for themselves.

Steve McLaughlin reflects on those times: “Thinking back about Hurley he was always one of those guys THERE but very stoic…quiet. In those days that wasn’t the case of most of the racers, me, KR, Pierce, Sheene, Smart, Ron Grant, Art Baumann, Aldana, Romero, et al, everyone vying for ‘talk time and centre of attention”.

LEVEL PLAYING FIELD

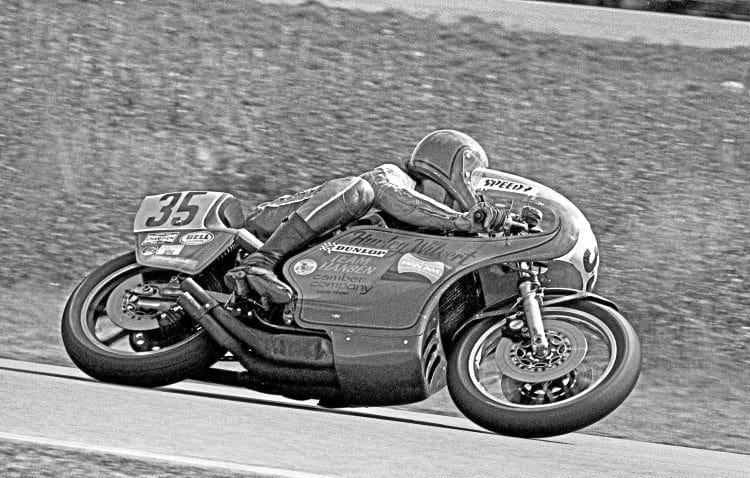

You would have expected that for 1974, Hurley would get an equal motorcycle? “Yes, I did, I got a bike equal to everybody else’s bike. Harold Sellers, a mechanic at Kawasaki, replicated the Seeley frame for me. I got it after the 1973 season so I had three bikes at Daytona in 1974.

“The stock Kawasaki, a special frame that Randy Hall had made, and the Sellers-framed bike. I ran them all in practice. The Randy Hall frame steered a little slow in the infield, but it was the most stable on the banking; the best one to ride for a race that long.”

The engine Hurley had built for Daytona was a real monster. “I’d done a lot of engine work over the winter. One was running the tallest gearing we had and it was still over-revving. I was afraid it was going to damage the crankshaft and I didn’t like running on part throttle as I was afraid it would seize. So I decided not to run it until I got a batch of smaller back sprockets.

“The thing had so much power I was having fun getting sideways coming out of the infield on to the banking, until one lap I got a little too energetic, high sided and got a concussion. It fell on the ignition side of the engine, damaged the ignition stator and bent the crankshaft.

“By this time I’d picked up a mechanic named George Vukmonovich. He replaced the crankshaft and I was a little loopy for a few days. We found that the ignition was from a 500 Kawasaki H1RA, and that wasn’t available anywhere. With the H2R ignition it would only pull the normal high gear, that 500 ignition was what was making it fast.”

The secret weapon was gone. “I’ll tell you how fast it was, I caught Duhamel on the back straight and passed him sitting up. It pissed him off severely. He came back screaming at the Japanese about ‘why is this guy’s bike faster than mine? My bike is supposed to be the fastest.’

“The Japanese came watching George take my bike apart and the only thing they could figure out was that we had bigger carburetors. So they had 38mm Mikuni carburetors air freighted for the other bikes. If I’d have had that motor for the race, I either would have won or it would have blown up. It would have made a second a lap difference. I finished 40 seconds behind Agostini, and it was a 48-lap race. I would have liked to have ridden the race with that motor.”

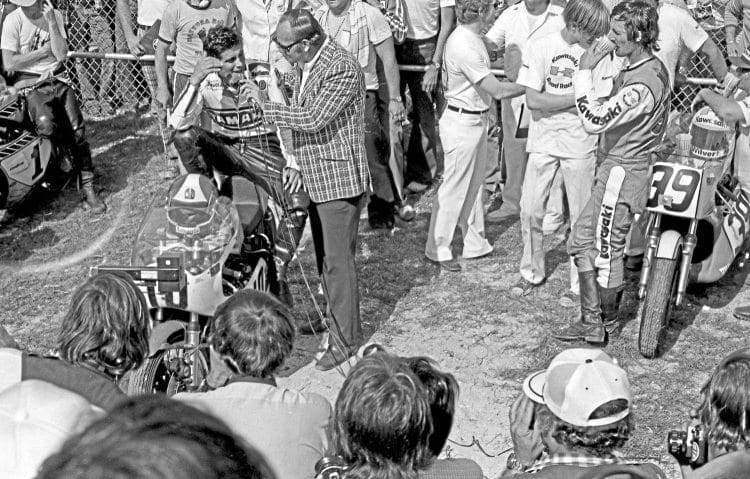

The race itself was somewhat anti-climactic. “I was on Dunlop tyres, as was Agostini; Kenny Roberts was on Goodyear. After the race the Dunlop guys said ‘you finished second, you have to go protest.’ During the race I was riding alone and actually started to get bored after a while. I’d be watching the leaderboard and saw I was third, I couldn’t see my pit board, but then the leaderboard said I was in second behind Ago.

“A couple of laps later I was shown third but nobody had passed me, so I couldn’t figure out what was going on. The Dunlop guys were telling me that I had passed Roberts when he went into the pits. I filed the protest and asked them to check the scoring.

“My guess is that Kenny’s stop put him out for the duration of a lap and the scorer just assumed they had just missed him. I mean, he was the national champion, and they didn’t want to screw him just because they weren’t paying attention. To this day the only ones that know for sure are Kenny’s guys. He was only 10 seconds ahead of me at the end of the race.

“I’m not sure Kawasaki team manager, Tim Smith, was too impressed as teammates were leading the race in front of me and crashed out (the infamous Yvon Duhamel and Art Baumann crash). I got paid a bonus because it was in my contract that I’d get a bonus if I was in the top three. It was $14,000 for getting third and I gave $4000 to George.

“The publicity from that race also got me noticed by a lot of people. It was the race that had the biggest collection of world champion riders, anywhere.”

Next was the Trans-Atlantic Match Races. “Gavin Trippe called me up and wanted me to go to the Match Races. I wanted to go, so I called Tim Smith my team manager and he said ‘well, you can go it if you want, but we don’t want you to go. If you do go, we will make things difficult for you.’ It was a big disappointment being the third rider on a three-bike team, excluded from events, even when doing so well.”

The season wasn’t as strong as 1973 had been. By mid-season there was a real epiphany about the tyres for Wilvert. “At Loudon I was sitting in the pits with my buddy Art Baumann. He asked me about tyres, and how after the fiasco at Daytona the year before I didn’t want anything to do with the Goodyear. He told me I should be trying those Goodyears, and he said ‘Hurley, you owe it to yourself to try them out.’ So, I tried them.

“Oh my God, it was like these tyres were made of glue and they would just stick to the road. I easily won my heat race and qualified second on the grid next to Roberts. I was so confident, so pumped. The two main guys to beat there were Roberts and Nixon. Shortly before the race, Nixon comes over to my van and he starts talking to me about my heat race. Typical Nixon… ‘Hey Wilvert, you did pretty good in your heat race, what’s going on?’

“I thought ‘that son-of-a-bitch is worried and that’s in my favour’. When I got to the starting grid I was ready to win my first AMA National. When the one-minute board comes up the crank starts rattling bad, I knew it was a rod. So I took off paddling to the side of the track. That was a real bummer.

“At Laguna Seca I didn’t finish because my countershaft sprocket came off. I had a little discussion with my mechanic about that after I told him to safety wire it and he didn’t. Kenny Roberts was right behind me on a 350 twin when that happened, and he almost hit me. He ran off the track onto the grass and dirt going up the long uphill to the Corkscrew. He managed to get it back on the track and kept going.

“Talladega was a 75-mile race and we were really tight on gas. The rear seat had an oil tank in it, held about a quart. I hooked up a line from that oil tank to the vent of the gas tank, so that the oil tank would empty first… yes, that’s cheating. It put too much restriction on the gas tank vent, so it started misfiring. So I pulled it off and gas came flying out all over the fairing, all over me.

So I had to take the vent off for the banking and then put it back on for turn one and the infield. I ended up finishing sixth behind Kenny Roberts, Don Castro, Jim Evans, Barry Sheene, and Cliff Carr.

“After the race I didn’t know if I would make another lap so I, and several other guys, cut the course to stay on the oval. Dennis Purdie was ahead of me and as we got to where the infield meets the banking, winner Roberts was coming out of the infield. Purdie stopped and I wasn’t expecting that.

“I hit him hard, bent my handlebars with my hands, and broke a bone in my wrist. Fortunately Dennis wasn’t hurt; it was totally my fault. For the last race at Ontario I decided to race with the broken wrist, cutting the palm out of the cast and taping it together with duct tape. That was the end of me riding the H2Rs.” There had been many lost opportunities at Kawasaki.

CHANGING BRAND

Suzuki came calling during the winter of 1974, so Hurley went testing at Ontario on the new laydown shock racer with the six-speed gearbox. “Barry Sheene ran about 75 miles and they wanted 200 miles on his bike, so they asked me to ride it.

“When I was headed out on to the track with his bike one of the mechanics was yelling to stop. There was a big bulge in the rear tyre tread. If I had gone out it might have failed on me. I did okay and they asked me to ride Daytona for them. They thought the tyre failure at Ontario was a one-off deal, until we got to Daytona when the tread came off and locked the rear wheel for Barry.

“I still wasn’t 100%, my hand kept hurting, and I didn’t have good strength in my hand. I’d just had the cast off two weeks before. It seized the centre cylinder one time. When I was visiting Barry in hospital he told me that he had tested two crankshafts in Japan and the one I had was crap. He was out of the race and wanted me to have the crank out of his bike.

“It had a little more power, but it would rev and had a bigger power band. In the race it seized before the first gas stop, when running about fifth.” That was the end of the road for Hurley as a factory team racer. “I liked the Kawasaki best of all, it handled better and stopped way better.”

Bob Pepper was a racer on the east coast and after Daytona, he set Hurley up with a Yamaha TZ750 as he had decided to quit racing. It was time to try the F750 World Championship. “I ended up going by myself, I was my own mechanic. I had to get the bike there, rent a van, and I ran into a friend from New Zealand who helped me a lot at the track.

“I was on the Dunlop tyres again and they told me to run these really low pressures. I started the first heat and the thing was awful, it steered like a truck. I had made arrangements with Team Kawasaki to help me with my pit stops, coming in the lap after Duhamel to get gas.

“My bike starts missing; how can I make six miles when it’s running out of gas? It went on three cylinders. I’m amazed as I’m almost to the last corner going 35mph on one cylinder and turned into pit lane as it quit. They put gas in and I ended up twelfth.

“During the interval between races we decided Yvon and I would move our pit stops up one or two laps, as Duhamel’s bike took almost the whole tank full. We changed the tyre pressure, which made it easier to go fast. I saw the signal for Duhamel to come in for gas, and I knew he was leading the race. When I came in the pit stop takes about six seconds, and nobody goes by on the race track. I suddenly realised that I had passed Duhamel and he hadn’t passed me back.”

Wilvert wasn’t leading by much. “There was about six guys about 50 feet behind me and about half of them tried to pass me in turn one. I just cut them off. The next four laps were probably the most intense racing laps of my entire life as they kept trying all over the place. I finally went into turn one too hot and four went by me. I ended up in fourth place overall.

“That was my swansong. I crashed at the Race of the Year at Mallory Park, and then in another race the engine seized from damage I’d done to it at Assen from over-revving it. Hurley finished fifth at Laguna Seca but then at Ontario I suffered heat exhaustion in the 100 degree heat”

CHANGING ROLE

During 1975, Hurley had also been helping with sorting out the new classifications for AMA racing, as Steve McLaughlin explains, “When I think of Hurley I think of all the practical stuff he did and I am sure like most of the AMA racing community he saw me as some “hollywoodesque” character… a bit larger than life. I could always see what looked like a bit of a laugh in his eyes at some of the things I said or did, but he was a dependable guy and it’s why I turned to him to write the F1 and Superbike rules.”

It was a new era for American motorcycle racing, however, for Hurley’s racing career, 1976 marked the end of the road. “I ran Daytona, determined after working on the TZ750 all winter, to do really well as it was just a hair slower than Roberts’ bike. At the start, I burned the clutch up and barely made it back to the pits. I didn’t really even make a lap.

“Then I went to Venezuela and I got heat exhaustion there too, got dizzy so I pulled in. I don’t remember too much about that as it was one of the low points of my life. I was out of money, I was supposed to race all the F750 races in Europe. I was expecting to make money at Daytona and Venezuela and I didn’t make a dime. That was the end, I quit.

“In 1979 a friend of mine, Philippe de Lespinay, knew Mr Morbidelli and he and Philippe had run a 125 several years before in the United States. Philippe convinced Mr Morbidelli that he could build a better chassis. Philippe designed the frame; I designed the Earl’s fork style front end. We needed somebody to make the frame and I knew a guy at Kawasaki who welded it up for us, in Kawasaki’s workshop.

“They were making stuff for their Grand Prix competitors in their own workshop. We sent it over to them; they put the bike together and ran it. There were some things Graziano Rossi and Mr Morbidelli liked about it, but there were other things they didn’t. The front end on it would have felt way different, and they put a regular steering head and telescopic forks on it, but they used the frame to my understanding.” Rossi ended up winning three Grands Prix in 250cc.

Wilvert worked for years as a Kawasaki dealer technical service adviser, before working for Yamaha in its golf cart division. He finished up his mechanical engineering degree in 1988 from Long Beach State. After that he did risk evaluation for clients at an insurance company until he retired. “In 2003, Dave Crussell, who races AHRMA, had a huge collection of vintage race bikes.

He was racing an H1R and found out about me and stopped by to visit on his way to Daytona. So I started racing AHRMA. He brought me an H2R to ride and I ended up last, the first time I’d ridden a race bike in 27 years, but I got interested again. I had a CL350 Honda that I converted into a 350 Vintage Club racer, and then started racing 500 in AHRMA. I won the West Coast division championship one year.

“In 2012 I got an invitation from Ronnie Russell of Team Collins and Russell to ride a Kawasaki H2R at the Festival of 1000 Bikes at Mallory Park, England. I was already going to Belgium to help my former sponsor, Dave Crussell race in a classic endurance race at Spa, so I accepted. The Mallory event was great fun. I had ridden at Mallory in 1975 so I already had experience on the track.

“When it came time for my event, it rained, the only time it rained the entire day! They red flagged it after two laps, but it was still great fun. It was great to see some of the English riders I’d raced with in the 70s there, like Mick Grant and Alex George. Ronnie Russell was apparently impressed with my performance at Mallory and invited me to participate in the Isle of Man Classic TT parade in August. As I already had other plans for August, we agreed that I would ride for Team Collins and Russell in 2013.”

The racing came to an end a year ago. “It got to be too expensive and time consuming but I raced the local club races until June 2015 when I crashed a 400 Kawasaki. I had my seventh brain concussion, and it was probably the worst one I’d ever had, so I decided I’ve got to quit doing this.

“I’m too aggressive, if somebody is ahead of me I have to catch them. I like street riding and I’m making plans for touring this summer out to Northern California and the central United States and the Dakotas. You can kind of do what you want to do when you retire.”

Read more News and Features online at www.classicracer.com and in the latest issue of Classic Racer – on sale now!