All fans of the ‘light and lean, green and mean’ Kawasaki tandem twins, that finally overcame Yamaha’s domination of the World 250 and 350cc Championships in the 1970s, are aware that these lithe little machines, with their game-changing inline cylinder layout, took a total of eight World Championships in those classes between 1978 and 1982.

Words: Randy Hall and Bruce Cox Photographs: Randy Hall Collection, Mick Ofield and Mortons Archive www.mortonsarchive.com

In the hands of South African, Kork Ballington, the KR250 and KR350 racers did the double in 1978 and 1979 while Germany’s Anton Mang won the 250cc title in 1980 before repeating Kork’s double 250/350 success in 1981 as well as winning the 350cc title again in 1982.

What most fans are not aware of, however, were that these successes were the culmination of a racing development programme that was begun by Kawasaki in Japan while working closely with the Kawasaki USA racing research and development team from as far back as 1973.

A programme that, even after it had nominally finished, led directly to KR250 successes in America for popular Aussie Gregg Hansford at Laguna Seca in 1977 and Daytona in 1978. Later in the early 1980s Eddie Lawson won numerous AMA lightweight class races culminating in two AMA Lightweight National Championships on the KR250 in 1980 and 1981.

Kawasaki USA racing manager and a highly valued R&D engineer at that time was Randy Hall, who had been originally hired to start Kawasaki’s first road racing department/team in the US for the 1971 season. This was after engineering Yamaha’s Rod Gould to the World 250cc Championship the previous year. He takes up the story from the end of the 1973 race season and writes…

In the Fall of 1973 I met with Ken Yoshida (lead engineer Kawasaki Racing Group), Lyndon Yurikusa (manager of Kawasaki Racing) and Yukio ‘HP’ Otzuki (senior engineering manager) to discuss the new racing bikes being developed in Japan for the 1975 season.

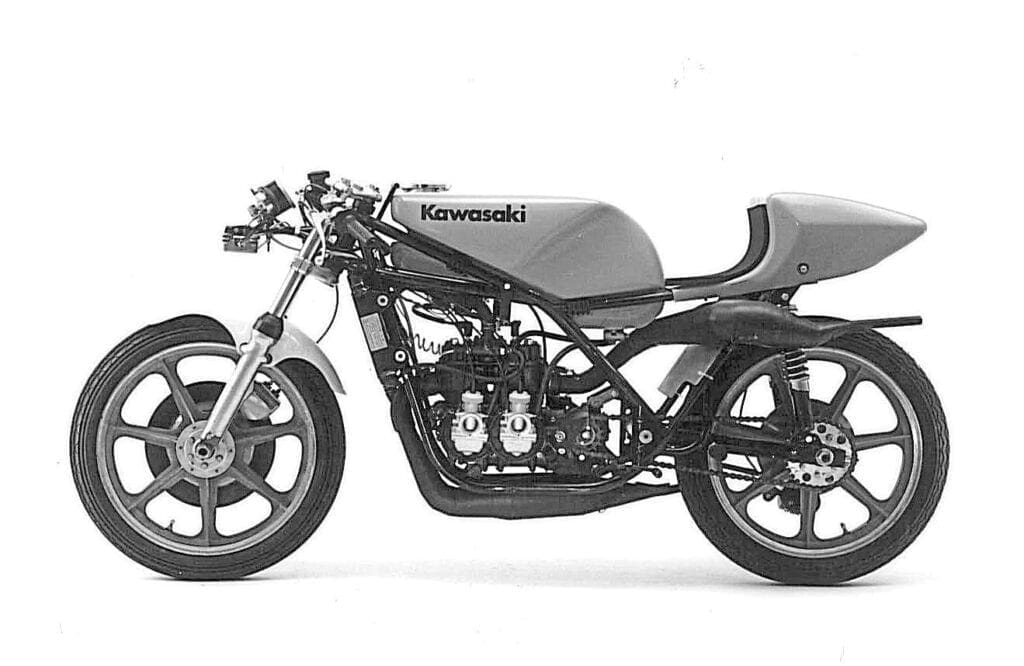

As well as a KR750 water-cooled version of the H2-R triple there was a secret KR250 in-line twin that was the primary design and responsibility of Ken Yoshida. This model, in particular, would need a lot of expedited development to go racing in little over a year’s time.

Engineering, building and developing both the KR250 and KR750 to race at Daytona in 1975 was a very challenging goal, especially in the glare of publicity that such a debut would inevitably create.

By October of 1974, both Kawasaki Heavy Industries in Japan (KHI) and Kawasaki Motors Corporation in the USA (KMC) had been working non-stop and in secret on the development of the KR250 and the KR750 throughout the preceding months when Kawasaki, and all other manufacturers, were given a major concession by the powers-that be.

The FIM, followed by the AMA, made a major change in the homologation rules by dropping the number of completed motorcycles that were needed to be submitted for inspection and verification down from 200 units to only 25. This change certainly took off a lot of the production pressures back in Japan but in no way did it allow any slowing down of the pace of development.

Kawasaki had racing history in Europe, including a 125cc World Championship in 1969 for Englishman, Dave Simmonds, and they wanted to build on that history. The world market for Kawasaki motorcycles was growing rapidly so an executive decision was made at KHI to build a 250cc racing model that would challenge Yamaha in both the 250cc FIM World Championships, and in the AMA Lightweight class.

Taking Up The Challenge

The engine for the KR250 model was being designed with a six-speed gearbox as required by FIM rules but in the initial 1973 meeting I pointed out that the AMA had no such rule, and we should actually make a seven-speed gearbox for American events that could be quickly and easily converted to a six-speeder for Europe.

I had two reasons for this: one was that the American banked super-speedway tracks require very high final gearing, which made the start of the race a clutch-burningly slow and difficult proposition.

Reason two, the more important one, was wind; a head wind on one straight knocking off lots of RPM/speed and a tail wind on the other pushing the bike along and causing the engine to exceed the RPM limit.

With seven speeds we could have a lower first gear for the starts, and sixth and seventh gears could be very close together for the wind factor on the straightaways. Everyone agreed this was a good idea, and they would make a seven speed transmission.

However, the design was too far along to make a cassette type of changeable gearbox. Therefore, the casing intended for the six-speeder was modified so that a special plug could be screwed into the bottom of the case and would fit into a groove in the shift drum that would lock out the seventh speed for FIM-sanctioned races.

Ken Yoshida was tasked with the responsibility of making the primary design of this new 250cc racing engine. Kawasaki had always liked the rotary valve type of inlet control, but realised from experience with the 250cc A1-R racer that the normal across-the-frame type of twin with a direct crankcase induction engine was inevitably going to be too wide.

It would be too difficult to optimise the handling and reduce the bike’s frontal area without restricting the airflow into the carburettors.

Ken therefore designed an in-line twin cylinder engine and correctly realised that, by off-setting the crankshafts by just 16mm, he could overlap the rotary valves and shorten the length of the unit.

Also by getting the two crankshafts as close together as possible the design would reduce the pitch-line velocity of the coupling gears. In an engine capable of 12,000rpm, the pitch-line velocity of these coupling gears is in a very critical speed range.

Water-cooling was necessary because of the inline design, and to obtain the maximum performance. To keep the engine weight down, the crankcases and rotary valve covers would be cast in magnesium.

A special type of ball bearing would be used on the crankshaft main bearings and these had two wedge shaped nylon rings around their outer diameter of the bearings that were designed to slightly crush when the two halves of the crankcases were bolted together as this would help to keep the roller-type main bearings in place in the relatively soft magnesium cases.

The design also offered the option of phasing the crankshafts with either a 180º firing order, or as a 360º twin-cylinder firing as a ‘big single’.

This would prove to be a valuable design option as the development of the KR250 proceeded. Design goals were that the engine be capable of 240bhp per litre, which would equate to 60bhp for 250cc, and that the motorcycle would have a dry weight of less than 100kg (220lb).

The beautiful little engine of the KR250 was Ken Yoshida’s baby, with another engineer in the racing department, Nagato Sato, being assigned the job of doing the detailed design drawings.

Ken’s inline twin basic design was extremely advanced for this time period with the proven high-performance rotary valve type inlet system that Kawasaki favoured. The finished engine design was very close as originally outlined to me in late 1973.

It featured ‘square’ cylinder dimensions of a 54mm bore by 54.4mm stroke and came with the suggested seven-speed gearbox.

Two 32mm Mikuni carburettors (later increased to 34mm) were mounted at a slight upward angle on the left -hand side of the engine, while the water pump, the Kokusan Magneto CDI ignition and multi-disc clutch were located on the right-hand side.

The cylinder head and the separate cylinder block were each cast in aluminium as ‘one-piece’ units for the twin-cylinder engine and the cylinder bores were coated using the ELEX process. The cylinders had three large transfer ports and a single exhaust port without a bridge.

There was a lot of study and testing carried out by Ken Yoshida and his staff on the phasing of the two individual crankshafts. On the plus side of the 360º phasing (with the pistons going up and down together) was the fact that it eliminated almost all vibration.

The torque output would fluctuate like a single-cylinder engine, but as first proven in dirt track racing, and later in road racing, the rear traction was noticeably improved and provided a harder acceleration off the corner.

On the negative side, this 360º phasing created a huge load on the crankshaft main bearings and crankcases, especially as the lightweight magnesium crankcases did not have the strength and hardness that aluminium crankcases would have had.

On the plus side of a 180º phasing (with the pistons alternately going up and down) the torque output was very even and the load on the crankshaft main bearings and crankcase was greatly reduced.

The smoother and lower torque peaks would allow a smaller clutch and the transmission could be lighter.

So at this time the concern over the lessened impact on main bearings and crankcase was the deciding factor to use the 180º phasing. It was also noted that push-starting the KR250 with the 180º phasing would be a lot easier than with 360º phasing.

This was an important factor to consider because the Grand Prix races at that time were dead motor starts requiring an easy-to-push and a quick-starting motorcycle.

One of the primary design goals was to keep the weight of the engine and total motorcycle as light as possible. To accomplish that, the crankcases, primary drive cover, rotary valve covers and carburettors were all originally cast in magnesium.

However, duration testing showed some problems with using magnesium for the crankcases, so after some analysis over the weight savings versus performance and durability, the crankcases were changed to aluminium.

Continuing the lightweight design theme, the front and rear brake discs were aluminium with a sprayed steel coating. The single front brake caliper on the right-hand fork was cast into the Kawasaki-designed-and-made aluminium fork sliders.

We used this one-piece fork with cast-in brake caliper design early in 1975, but as the season progressed and the KR250 got faster, better brakes would be required and we went back to the more conventional set-up that permitted the fitting of stronger calipers and bigger discs.

Like their bigger KR750 brothers, all 25 KR250 motorcycles produced were fitted with Koni suspension units and Morris Mag wheels.

Testing Times

After a big launch at the Los Angeles Playboy Club for the bikes that would be used by the road racing and motocross teams for the 1975 season, we left Southern California in February for the cross-country drive to Daytona in Florida.

We had rented the track there for testing, as per a plan that I had managed to get approval for in the meeting at KMC’s R&D Center way back in 1973.

I had pushed strongly for it back then as I always felt that pre-race testing on-site would be the most productive in preparing for the March Daytona 200 race, particularly considering the short time before the first race for these new racing models.

If the testing showed a need for modified parts, then there possibly would be time to get them made, and sent by air from Japan to Daytona as quickly as sending them to California. This actually turned out to be the case.

With our two US team riders, Yvon Duhamel and Jim Evans, entered in both the Lightweight race with the KR250, and in the Daytona 200 on the KR750, I needed two new race mechanics on the KMC Racing Team. Fortunately, I did not have to look far as Steve Johnson, an experienced road race mechanic, was working at KMC on the motocross race team.

In 1971, I had turned down a request from Phil Read to return to Europe as his mechanic and instead had arranged for Steve Johnson to mechanic for Phil in what turned out to be his successful World 250cc Championship campaign as a private rider.

Four years later, I was able to get Steve moved over to the road race team for 1975 and was also able to get Jeff Shetler, a former US Air Force aircraft mechanic, switched from the Kawasaki Technical Services department to complete the team.

Right from the start of our 1975 Daytona testing, however, things did not go well with the KR250, which was running hot and losing power as the engine temperature rose. By the end of the first day we had just about everything in pieces trying to solve these problems.

That evening Ken Yoshida began running up a huge phone bill talking to KHI in Japan – and soon that call became a nightly thing.

Before its actual Daytona race debut, we did two things to reduce the running temperature of the KR250. Firstly, KHI shipped new drive gears for the water pump from Japan that would increase the flow of coolant through the radiator.

Secondly, we suspected that the close fitting of the crankcase cavity around the gears that connected the two crankshafts together, plus the very high pitch line velocity of these gears, was creating what was in effect a very high-speed oil pump – an oil pump with nowhere for the oil to go.

The oil got so hot that it melted the plastic rings around the crankshaft main bearings.

We made some pre-race cooling system modifications, went to lighter transmission oil and lowered the transmission oil level. All were purely temporary modifications that lowered the running temperature enough for us to at least race the KR250.

However, the engine was running hotter than the desired 80ºC for optimum performance and would not pull a maximum rpm of more than10,000rpm. We had no illusions about a dream debut – and that was certainly the case.

Our newly signed young rider, Jim Evans, had a heavy crash in practice, suffered concussion and was out of the race – sadly another crash several weeks later at the Paul Ricard Circuit resulted in similar injury, and finished what was likely to have been a very successful international career.

Jim was replaced in the Kawasaki team by another Californian, Ron Pierce, who would start the Daytona race alongside Yvon Duhamel. The KR250 was still a long way from being as ready as we would have liked and it was obvious that the bike was not going to trouble the Yamahas. Or even, as it happened, a new two-stroke twin built by Harley-Davidson’s subsidiary, Aermacchi in Italy.

Kenny Roberts won the Daytona race for Yamaha, with Gary Scott second on the Harley and Steve Baker third on another Yamaha. Yvon dropped out of the race early on, while Ron Pierce made it to the finish, almost unnoticed in 13th place. Not a great debut for our proposed ‘Yamaha beater’!

The next race on the US schedule was not until Laguna Seca in August, so at least we had some time to work via parallel programmes in California and Japan to get closer to our goal.

Ken Yoshida and I agreed that KHI and KMC would each do a separate development and testing programme and share information. KHI had the resources for designing and making new parts to improve the power and reliability.

In turn, what Steve and I could do with our KMC resources was to focus on getting more horsepower with engine porting modifications and making different exhaust pipes to test.

At the same time, we would also work on suspension and chassis improvements. For testing on local circuits, such as the Riverside and Orange County raceways, we had our California-based team rider, Ron Pierce, and ex-pat Englishman, Martin Carney, who was working at KMC.

Martin had been British 125cc National Road Race Champion and a friend since my European days. Closest to KMC was the Orange County Raceway and drag strip, which was good for power-oriented speed and acceleration testing on their simple road race course.

For more demanding chassis tests our other option was the Riverside International Raceway which was further away, but which had more challenging high-speed corners.

As always, some things worked in testing and some didn’t. Putting a larger radiator from the KR750 on to the KR250 didn’t make any measurable difference in bringing down the running temperature. It really didn’t fit the slimline profile of the smaller bike.

What did finally solve our problems with overheating was a new design of water pump and a thicker radiator that greatly increased the cooling area, both changes resulting from development and testing in Japan.

Meanwhile, in California, we spent much of our available development time fabricating new exhaust expansion chambers and testing them both on the dyno and on the track.

During my time in Europe with Rod Gould and Yamaha, I had got to know Dr Gordon Blair at Queen’s University, Belfast, and stayed in touch with him.

His advice along with papers and engineering articles that he had given me were extremely helpful to my understanding how two-stroke exhaust pipes worked, and what to change to affect the power…not just at the top end but at other points in the rev-range.

I would make drawings of rolled metal cones that we wanted to try, fax them to Aircone, a specialist exhaust pipe fabricator and in less than a week we would get them back to weld together. I can’t remember how many different pipes we made but I do know that I got really good at TIG welding thin metal in the process.

Finally, we came up with a pipe design and port timing that got the engine pulling well all the way up to 12,000rpm – some 2000rpm up on what the bikes had been hitting at Daytona but this threw up a new problem during testing.

With the added revs, the front expansion chamber would crack all the way around and through the tapered head pipe where it joined the engine. Once the pipe cracked like that, the pipe lost its pressure waves, and the power went way down.

Strangely, it was only the front cylinder exhaust chamber that cracked; the rear one was fine. So, I made a front pipe from heavy 16-gauge material. And it still cracked!

After studying the pipe problem, I decided the issue was the direction of the engine vibration. The highest amplitude of vibration on this 180º phased engine was in a front-to-back direction, not up and down. The rear pipe went more or less straight back in the frame in the same direction as this vibration and so absorbed these forces.

The front pipe curved under the engine and was fastened to the frame at the back. So the rear part of the pipe was restricted in movement and the front part of the pipe was trying to move back and forth at a high frequency. The result was concentrating stress in the middle of the front cone and tearing the pipe apart.

To cure this problem, I designed and made what was basically a cradle that fastened to the bottom of the engine using the crankcase bolts. The front exhaust pipe was then hose clamped to this cradle and the rear frame mount was discarded.

Now the entire front exhaust pipe was only mounted to the engine itself and would vibrate in frequency with it. After this fix we experienced no more cracked front pipes, even when we made them from thinner 20-gauge material.

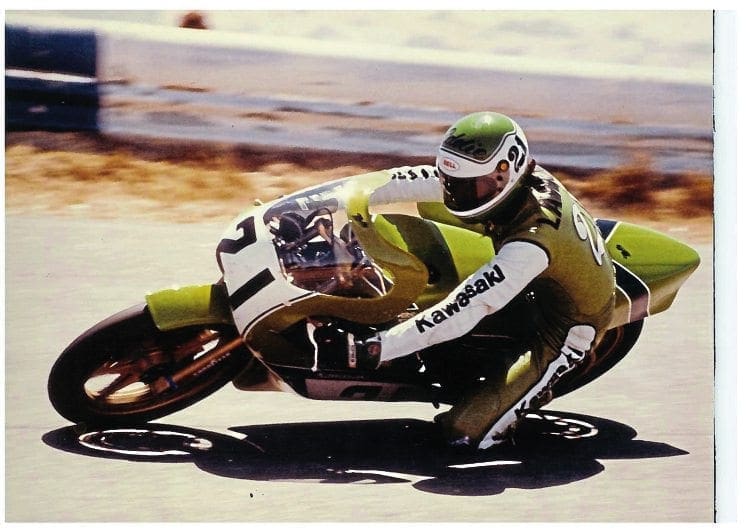

By August and the race on the famous Laguna Seca course near Monterey in Central California, the combined improvement work done by KHI in Japan and our US team now had us on a competitive footing with the 250cc Yamahas as far as power was concerned.

During practice, however, both Yvon Duhamel and Ron Pierce were experiencing fading of the front brake on this track, which has corners needing some hard braking.

Nevertheless, Yvon won the second heat race and, as Kenny Roberts was second on the Yamaha it was a well-deserved first win for the KR250. And it was one made even sweeter by the fact that Ron Pierce was third.

The main event was an exciting race with Yvon and Ron running right up with Kenny and Steve Baker on the Yamaha US and Yamaha Canada works bikes, although brake fade in this longer race did see Yvon and Ron drop to third and fourth at the finish.

However, we were obviously making progress with getting the KR250 running up to its true winning potential. In fact, Yvon thought he could have won the race except for the fading of the front brake. All things considered, we had every reason to be satisfied with a podium finish in what, after all, was only the bike’s second Championship outing.

The final Championship race of the year would take place in early October at the Ontario Motor Speedway in Southern California, where there would be two short qualifying heat races and then a main event of approximately 50 miles.

After the promising results with the KR250 at Laguna Seca, we were all anxious to see our hard development work pay off with a win in an AMA race against the well-proven 250cc Yamahas.

Our hopes were even higher as Ron Pierce had won a non-Championship race earlier in the year at Loudon, New Hampshire on a KR250 that had been provided to Kevin Cameron, a well-known two-stroke tuner in the New England area.

Things certainly looked good after both heat races were won by Kawasaki riders. Masahiro Wada from Japan took the first from the Harley-Davidson/Aermacchis of Walter Villa and Gary Scott, while Yvon Duhamel won the second ahead of Steve Baker. Not only that but English Isle of Man TT star, Mick Grant, had come over with Kawasaki UK bikes and finished third.

Those heat race wins were the first for a KR250 at an AMA Championship meeting. The question was, could we also win the main event? Sadly, the answer was no. It was disappointing indeed to see Wada drop out of the race while in position for the win because of a failed ignition coil.

Yvon also had a mechanical problem that caused him to drop out of the race, but at least Mick Grant hung in there for a great third place.

Two podium places in three races meant that all in all, and thanks to the collective efforts of Kawasaki teams in Japan, the USA and the UK, we had made significant steps over the summer towards making the KR250 a winner in any company.

But obviously we were still going to be busy over the coming winter.

One area we went to work on was in weight saving. Steve Johnson and I took Yvon’s 1975 bike, and decided to convert it to a single-shock rear suspension. Taking into account the already light weight of the motorcycle and the power level, we decided that the swinging arm and frame would work just fine with only one suspension unit on one side of the swinging arm.

We did some minor bracing and installed one Monroe air-spring suspension unit. I don’t remember the actual weight savings, but it was a significant amount and Yvon liked the air spring on the Monroe shock absorber.

There was also another benefit in getting rid of one of the shocks. After some frame modifications in the rear, we were able to make the bike even more compact by making a new rear exhaust pipe that tucked in tighter to the rear wheel.

It was a project that worked well, but would only be an interim measure as engineers back in Japan were already busy working on what would be revealed in 1978 as Kawasaki’s famous Uni-Trak rising rate rear suspension system. That system used a bell crank and a single shock absorber behind the engine.

There were also some modifications to the engine over the winter including a special cylinder head that Steve and I called our ‘trench port’ design. The squish area of the combustion chamber was now only on the sides and front of the head.

A trench collected the fresh charge coming up the back of the cylinder from the transfer ports and aimed it at the spark plug. The angle of the spark plug was no longer straight up and down, but angled back toward the fresh incoming charge. It resulted in extra torque and made the power curve a little broader for improved acceleration of the corners.

Steady Development

As the 1976 season started, I was glad that Steve and I had completed so many modifications and improvements to the KR250 in 1975 as he was needed back in the motocross racing department. Fortunately, we were able to draft Martin Carney full-time into the road racing team, which meant we had both a good mechanic and a test rider in one person.

That season proved to be much more valuable for the steady development of the bikes rather than in chalking up wins. But at least it was one in which the KR250 proved that it was on a par with the fastest Yamahas of Kenny Roberts and Steve Baker, even though it could not consistently win races.

Yvon Duhamel did win his heat race on the tight little track at Loudon, New Hampshire and rode to a great second place in the final.

Try as he might, however, he just could not force his way past Steve Baker’s Yamaha. Still, it was one step closer to our goal of an AMA win than we had got in our first season. For the final race of 1975, at Riverside in Southern California we made a major change to Yvon’s KR250.

Ken Yoshida wanted us to test re-assembling the crankshafts to the 360º phasing, with both pistons going up and down together.

KHI was planning that the 1977 model KR250s would have the crankshafts assembled to this phasing, and Ken wanted our evaluation ahead of time – which shows that racing the KR250s in the USA was still very much just a development programme in the minds of the engineers in Japan.

We were actually developing future World Championship racers under the scrutiny of the American race fans.

A new low-drag ignition for the 360º phasing was sent to us. Otherwise the main mechanical components were unchanged (though the crankshafts in the 1977 model would benefit from upgraded main bearings). On the track this new phasing completely changed the sound the motorcycle made as it was now firing like a big single and sounding like a motocross bike.

Yvon liked the reduced level of vibration and the way the motorcycle accelerated off the corners so my race report to Ken was a positive recommendation for the crankshaft phasing change.

At the Riverside event, Yvon took a second in his heat race and then got on the podium again in the main event by finishing third behind the Yamahas of Kenny Roberts and David Emde.

As the 1976 season showed, there were still problems to be solved but the KR250 was winning shorter heat races and sharing the podiums with the fastest Yamaha riders in main events.

There was still much to do before they would be winning World Championships but the potential was already showing.

That was satisfying enough for me as I was headed back to the research and development work department because the KMC management had decided that it would no longer support a USA road racing team in 1977.

It was the right decision considering that the sports motorcycle sales market in the United States would soon go primarily towards four-stroke motorcycles.

Now that KMC would not be road racing, it was time for KHI to switch their primary road racing development and racing support to the other very active national distributors who had created their own road racing teams.

In the UK, for example, Stan Shenton had a very strong team with Mick Grant and Barry Ditchburn while Neville Doyle in Australia had Gregg Hansford and Murray Sayle riding in European events.

It was time for Kawasaki to seriously challenge for the FIM World Championships which, after all, was the primary reason for creating the KR250 and the future KR350 model. And Europe was where the challenge needed to take place.

From my own viewpoint, I was more than pleased with what our team had done to help lay the foundations of this challenge and, just because KMC was no longer racing, that didn’t mean there were no Kawasaki’s racing in either the USA or Canada during 1977.

You can imagine how thrilled the whole California crew and I were when Gregg Hansford came to Laguna Seca and gave the KR250 the American main event win that we had all been waiting for.

It might have taken until the bike’s third season to achieve this but remember that there were only three US races for us to contest in our first season and just four in our second. In less than 10 AMA races, the KR250 was where we had always felt that it could be. This fact was emphasised when Gregg came back with the little twin in 1978 and won the 250cc race at Daytona.

From my own viewpoint, it was even more satisfying to bow out with another win. Yvon Duhamel, with whom I had been so closely connected for so long, had come out of his 1977 retirement for the Canadian Grand Prix at the historic Mosport circuit near Toronto.

So off I went to Canada to mechanic for him in his final farewell race in front of his devoted home fans.

When he won the Lightweight race with the KR250, it was a wonderful moment for us, and all the guys back in California who had worked on ‘the little green meanie’. A perfect chapter point for me to close the book on a very interesting and satisfying period in my career.

In the next issue: Time for Randy to begin another chapter by returning from the research and development department to manage the Kawasaki US Superbike team.

Sincere thanks to Mick Ofield for his stunning illustrations in this feature. Before he left the UK for the sunnier climes of California Mick worked as a designer at Norton Motorcycles, from 1972 to 1980, after graduating from art school.

Now retired from designing and racing, at which he enjoyed a long and successful career both sides of the Atlantic, one of his hobbies is creating highly detailed illustrations of famous road race motorcycles.

You can find Mick on Facebook at www.facebook.com/RoadraceMotorcycles or [email protected] or USA 931-224-0477. Please tell him Classic Racer sent you.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicracer.com and in the latest issue of Classic Racer – on sale now!